Edvard Munch è conosciuto come il pittore della sofferenza interiore, di un dolore e una malinconia che è riuscito a esprimere con forza attraverso i suoi quadri. Un disagio esistenziale in cui si è ritrovato l’essere umano del Novecento, infatti il suo dipinto “L’urlo” è diventato l’icona di un grido universale. La parola “esprimere” è qui emblematica, perché sarà proprio Munch ad aprire le porte ad un nuovo tipo di pittura, quella espressionista, cioè che esalta, attraverso colori accesi e una realtà deformata, le emozioni del pittore stesso.

Nella mostra “Munch – Il grido interiore” i visitatori potranno osservare cento sue opere, quadri e incisioni, alcune delle quali molto famose. Una panoramica che permette di avere una visione ampia del suo lavoro. L’esposizione non si sviluppa cronologicamente, ma per tematiche, perciò in ogni sezione è possibile vedere opere di tempi diversi, dove lo stile cambia (consiglio: leggere sempre la data d’esecuzione).

Alcuni lavori hanno una spiegazione scritta che però, purtroppo, è il punto debole di questa bella retrospettiva, in quanto spesso non fornisce ai visitatori gli elementi fondamentali per capire ed interpretare l’opera stessa.

Edvard Munch nasce a Kristiania (l’attuale Oslo) il 12 dicembre 1863. Studiò nella Scuola Reale d’Arte nella stessa città e fu influenzato (come si vede nella mostra in alcune opere giovanili) dagli impressionisti e post-impressionisti che conobbe durante le sue due permanenze a Parigi.

Letali per la sua sensibilità e fragilità psicologica furono la morte della mamma quando lui aveva cinque anni, la morte della sorella Sophie nove anni più tardi (entrambe decedute per tubercolosi, un vero flagello a quell’epoca) e anche la paura di ereditare, o di trasmettere a possibili figli che non ha mai voluto, la malattia mentale di cui soffrivano membri della sua famiglia. Successivamente, nel 1890 mentre era a Parigi, muore anche il padre, fatto che lo affliggerà terribilmente.

“Fin dalla nascita gli angeli dell’angoscia, del dolore, gli angeli della morte sono stati al mio fianco, seguendomi quando giocavo all’aria aperta, sotto il sole di primavera, nel chiarore dell’estate. Mi erano accanto la sera quando chiudevo gli occhi e mi sussurravano minacce di morte, inferno e dannazione eterna, e spesso mi capitava di svegliarmi di notte e fissare con terrore la stanza intorno a me. Sono finito all’inferno?” scrive l’artista in un suo quaderno.

A causa del suo malessere interiore, Munch aveva una dipendenza dall’alcool che non faceva che aggravare, in un circolo vizioso, il suo stato d’animo. Aveva anche un rapporto controverso con il “gentil sesso”, come si evince dai suoi quadri, dove la donna è rappresentato come una femmina fatale che porta l’uomo alla perdizione. In particolare, ebbe una relazione importante con Mathilde Tulla Larsen, un rapporto turbolento e con un esito drammatico: in un’ultima lite nel 1902 partì un colpo di pistola che ferì Munch a una mano. Questo non fece che aggravare la sua precaria situazione psicologica e nel 1908 lo stesso artista si accorge di essere ai margini della vera follia in quanto soffriva di allucinazioni e si sentiva perseguitato. Decise perciò di farsi ricoverare nella clinica del dott. Daniel Jacobson: fu la sua salvezza, e dopo otto mesi poté fare ritorno in Norvegia completamente ristabilito, tanto è vero che anche il suo stile pittorico cambiò, mostrando colori più vivaci e situazioni più tranquille, di una vita vissuta con serenità.

Munch visse gli ultimi anni in una sua proprietà vicino a Oslo, immerso nella natura, fino al 23 gennaio 1944, quando muore a ottant’anni.

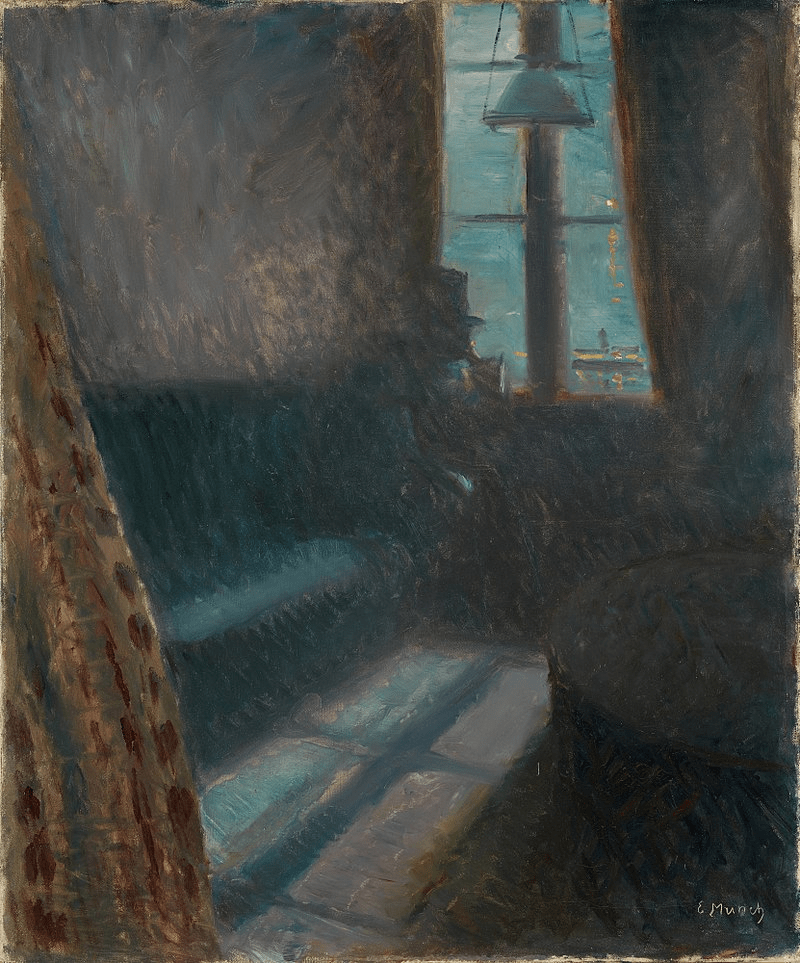

Edvard Munch, “Chiaro di luna. Notte a Saint-Cloud“

Mentre era a Parigi, nel dicembre del 1890, a Munch venne comunicata la morte di suo padre. Non avevano avuto un buon rapporto, ma, forse anche per questo, l’artista soffrì molto. Era un altro lutto di una lunga lista, che lui stesso elenca: la madre, la sorella Sophie, il nonno, ed ora il padre. Inoltre sentiva un senso di colpa causato dal non aver potuto tornare in Norvegia in tempo per assistere al funerale. Dipinse un olio su tela dal titolo “Notte a Saint-Cloud”: una stanza nella notte, una lieve luce che proviene dalla finestra con un uomo in controluce che guarda fuori, prevalgono i toni dell’azzurro e del blu.

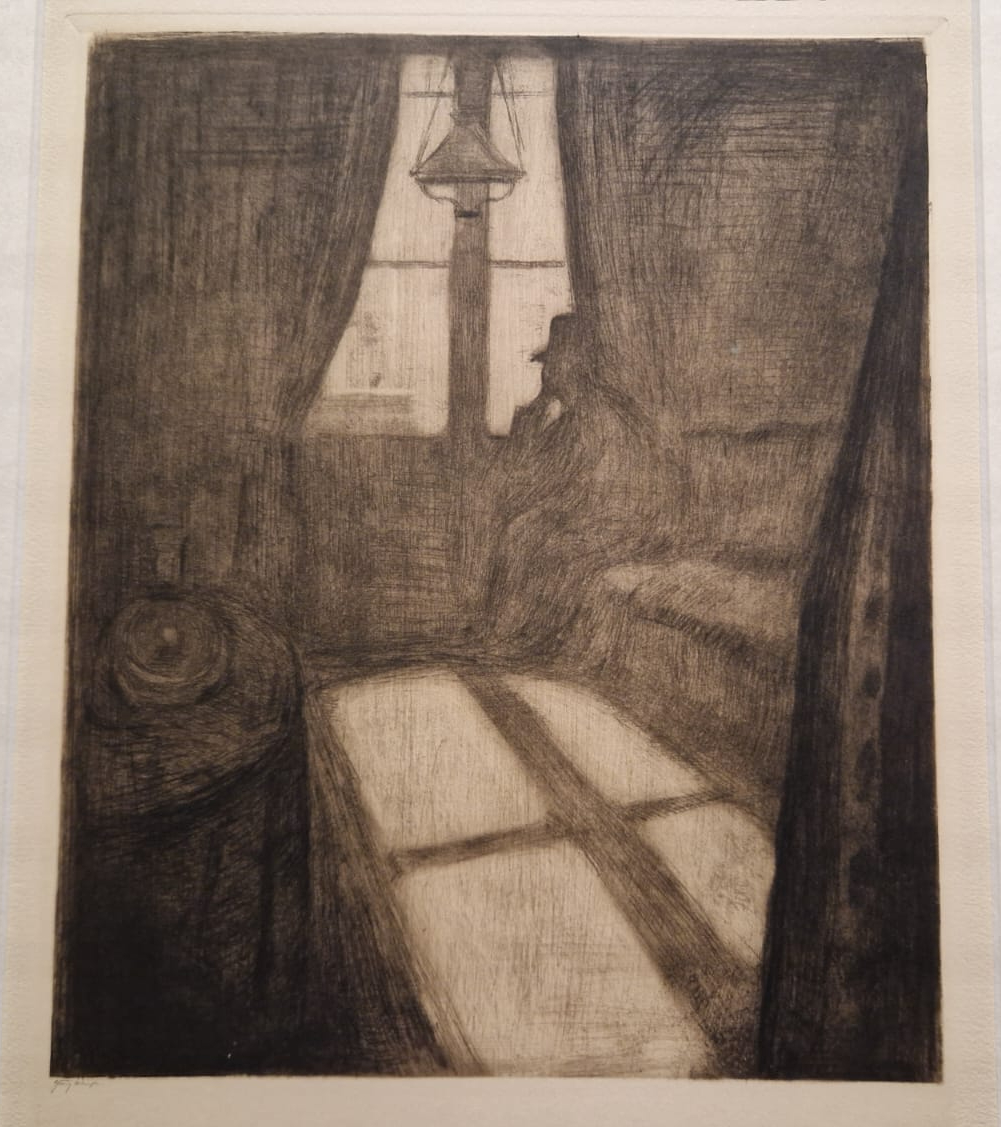

Dopo cinque anni, Edvard riprende il soggetto e realizza un’acquaforte, presente alla mostra.

Munch amava la tecnica dell’incisione e ne fa ampio uso, specialmente xilografie e acqueforti. Ci sono molti suoi dipinti ad olio che sono stati poi ripresi e riprodotti con delle incisioni, come ad esempio “L’urlo”, “Madonna” o “La bambina malata”, anche quest’ultima visibile nell’esposizione. Spesso le incisioni hanno la caratteristica di raffigurare il soggetto del dipinto allo specchio, perché, quando si stampa, l’immagine inverte la destra e la sinistra, ed è proprio il caso di “Chiaro di Luna. Notte a Saint-Cloud”.

Anche nell’acquaforte, come nel dipinto, la nostra visuale si apre su una stanza, la cui oscurità è in parte vanificata dalla luce lunare che proviene dalla finestra. Noi siamo degli osservatori esterni, silenziosi, che non vogliono disturbare l’intimità dell’uomo seduto sul divano; proprio per questo una tenda, sulla destra, ci divide dal suo spazio, che cogliamo come intimo. Sulla sinistra si intravvede un tavolo tondo coperto da una tovaglia, sopra vi è posato un oggetto. In alto pende un lampadario, perfettamente allineato con il telaio della finestra, a sua volta in parte coperta da dei tendoni. A destra è presente un lungo divano su cui siede l’uomo, che ha un braccio piegato appoggiato al bracciolo così da reggere il volto. Porta un cappello e guarda fuori, nella notte, probabilmente perso nei meandri dei suoi pensieri. A terra, evidente, si staglia l’ombra della finestra che crea così una grande croce sul pavimento.

Non è difficile collegare la morte del padre con questa figura maschile, quasi che fosse la sua apparizione in una notte parigina rischiarata dalla luna, a Saint-Cloud, dove Edvard viveva. La croce richiama la sua dipartita, ma anche la sua fede religiosa, motivo di litigi e incomprensioni con il figlio.

L’opera riesce a trasmettere tutta la malinconia e il senso di mancanza che si provano quando si perde una persona cara.

Edvard Munch is known as the painter of inner suffering, a pain and melancholy that he managed to express powerfully in his paintings. An existential malaise in which 20th century man found himself, his painting “The Scream” has become an icon of a universal cry. The word ‘express’ is emblematic here, because it was Munch himself who opened the door to a new type of painting, the expressionist, that is to say, the painting which, through bright colours and a distorted reality, exalts the painter’s own emotions.

In the exhibition ‘Munch – The Inner Scream’, visitors will be able to see one hundred of his works, paintings and engravings, some of them very famous. An overview that gives a broad view of his work. The exhibition is not chronological, but thematic, so in each section you can see works from different periods, where the style changes (tip: always read the date of completion).

Some of the works have a written explanation, which is unfortunately the weak point of this fine retrospective, as it often does not provide the visitor with the basic elements for understanding and interpreting the work itself.

Edvard Munch was born in Kristiania (now Oslo) on 12 December 1863. He studied at the Royal School of Art in the same city and was influenced (as can be seen in the exhibition in some of his early works) by the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists he met during his two stays in Paris.

The death of his mother when he was five, and of his sister Sophie nine years later (both of whom died of tuberculosis, a real scourge at the time), as well as the fear of inheriting or passing on to any children he might have, the mental illness suffered by members of his family, were lethal to his sensitivity and psychological fragility. Later, in 1890, while he was in Paris, his father also died, a fact that affected him terribly.

“Ever since I was born, the angels of torment, of pain, of death, have been at my side, following me when I played outdoors, in the spring sunshine, in the glow of summer. They were beside me at night when I closed my eyes and whispered threats of death, hell and eternal damnation, and I often woke up in the middle of the night and stared in horror at the room around me. Was I in hell?” the artist wrote in one of his notebooks.

Because of his inner malaise, Munch became addicted to alcohol, which only worsened his mental state in a vicious circle. He also had a controversial relationship with the ‘fairer sex’, as can be seen in his paintings where the woman is depicted as the femme fatale leading man to his doom. In particular, he had an important relationship with Mathilde Tulla Larsen, a turbulent one with a dramatic end: in a final quarrel in 1902, a gunshot wounded Munch in the hand. This only aggravated his precarious psychological situation, and in 1908 the artist himself realised that he was on the verge of madness, suffering from hallucinations and feeling persecuted. He therefore decided to be admitted to Dr Daniel Jacobson’s clinic: this was his salvation, and after eight months he was able to return to Norway fully recovered, so much so that his painting style changed, showing brighter colours and calmer situations of a life lived in serenity.

Munch lived his last years on his property near Oslo, surrounded by nature, until 23 January 1944, when he died at the age of eighty.

Edvard Munch, “Moonlight. Night in Saint-Cloud“

While in Paris in December 1890, Munch was informed of his father’s death. They had not had a good relationship, but perhaps because of this the artist suffered greatly. It was yet another bereavement in a long list that he himself listed: his mother, his sister Sophie, his grandfather and now his father. He also felt guilty about not being able to return to Norway in time for the funeral. He painted an oil on canvas entitled ‘Night in Saint-Cloud’: a room at night, a faint light from the window with a man looking out against the light, blue and light blue tones predominate.

After five years, Edvard returned to the subject and produced an etching that is on display in the exhibition.

Munch loved the technique of engraving and made extensive use of it, especially woodcuts and etchings. There are many of his oil paintings that were later taken up and reproduced with etchings, such as ‘The Scream’, ‘Madonna’ or ‘The Sick Little Girl’, which are also on display in the exhibition. The engravings often have the characteristic of showing the subject of the painting in a mirror, as the image is reversed right and left when printed, and this is precisely the case with ‘Moonlight. Night at Saint-Cloud’.

In the etching, as in the painting, our gaze opens into a room whose darkness is partially obscured by the moonlight streaming in through the window. We are outside, silent observers who do not want to disturb the intimacy of the man sitting on the sofa; this is precisely why a curtain on the right separates us from his space, which we perceive as intimate. On the left, we see a round table covered with a tablecloth, on which an object is placed. Above it hangs a chandelier, perfectly aligned with the window frame, which is partly covered by curtains. To the right, there is a long sofa on which the man is sitting, one arm bent over the armrest as if holding up his face. He is wearing a hat and looking out into the night, probably lost in thought. The shadow of the window is clearly visible on the ground, forming a large cross on the floor.

It is not difficult to associate the death of his father with this male figure, as if it were his apparition on a moonlit Paris night in Saint-Cloud, where Edvard lived. The cross is a reminder of his departure, but also of his religious faith, the cause of his quarrels and misunderstandings with his son.

The work succeeds in conveying all the melancholy and sense of loss one feels when one loses a loved one.